More than 18 million people die each year from heart attacks and strokes

You’ve been redirected. LINKScommunity.org is now part of resolvetosavelives.org.

Resolve to Save Lives works to end preventable death from cardiovascular disease. Few global health organizations work in cardiovascular health, and fewer still work across both prevention and treatment.

There is a tremendous amount of work to be done—with limited political attention and scarce funding. Heart health hasn’t yet benefitted from the focused global action that has led to big improvements in infectious disease control.

We focus on proven, high impact interventions:

50%

Improving control of high blood pressure from 14% to 50% worldwide

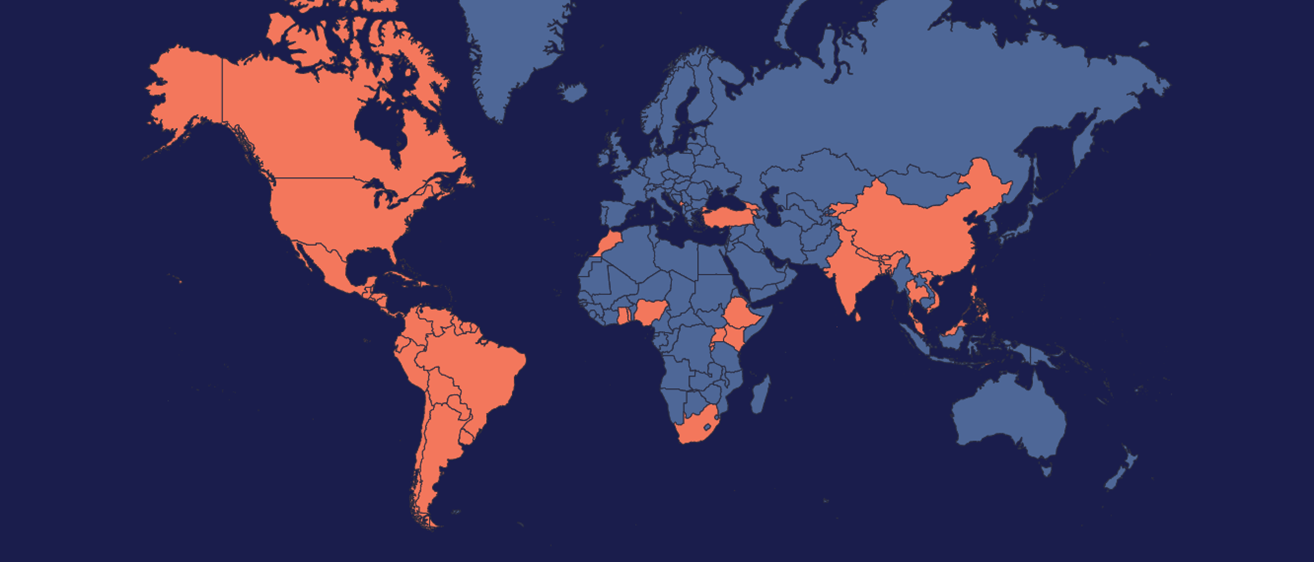

High blood pressure, or hypertension, kills more people than all infectious diseases combined. We have supported improved care of more than 19 million people living with hypertension, with programs and policies in 32 countries.

30%

Reducing salt intake by 30% globally

High salt intake raises blood pressure, the leading risk factor for heart disease and stroke. We supported WHO to develop the first global “gold standard” for what maximum sodium levels should look like across different types of foods. We have funded research into low sodium alternatives to popular condiments (such as fish and soy sauce) and supported research and advocacy for warning labels on high-salt packaged foods.

0

Eliminating trans fat from the global food supply

Artificial trans fat—a compound used in processed foods, fats and oils that increases the risk of heart attack and death—can be replaced with healthier options without affecting taste or increasing costs. Since we partnered with the World Health Organization to launch the REPLACE initiative in 2018, an additional 2.8 billion people have gained protection through policies eliminating trans fats.

100M

Together, these three strategies can save 100 million lives globally by 2050.

How many lives can be saved in your country?

Use our Lives Saved Calculator to see how many lives can be saved in your country by improving blood pressure control and reducing salt intake.

How we work

We work with global and local partners to develop cardiovascular disease prevention programs based on current evidence-based practices that address the needs of the population and the health system. Our global partners include the World Health Organization, John’s Hopkins University, the Global Health Advocacy Incubator, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Pan American Health Organization.

Tools to take action

Explore our resource libraries for Hypertension Control, Sodium Reduction and Trans Fat Elimination.